|

This site is best

viewed at 800x600

and 16 bit color.

| |  | This month's award goes to Wing Commander Zahid Butt of the Pakistan Air Force, for his work done back in 1965, right before the war with India. With the increased tensions and the Pakistan Army already in Kashmir, the drop zone was made even more treacherous with the possibility of ground fire and Indian air interception. The PAF collection of C-130s was deemed too important to waste away during daylight operations over Kashmir. The PakArmy came to the conclusion that aerial resupply was completely out of the question, as flying those C-130s into Kashmir at night would be suicidal, with the mountains stretching up as high as 26,660 feet (Nanga Parbat). Wing Commander Butt had a different idea, though.

Having flown through those mountains in the past using old C-47 Dakotas and Bristol Freighters, he thought that with the added power of the turboprop engines and using the weather radar of the C-130, a night drop would be possible. Here is his story, in his own words: | "I'd been experimenting on these lines on my own, without telling anybody and been kicked off sometimes, before Air Vice Marshal Nur Khan took over, for having done a few things which were not the normal way of flying transport airplanes. I had worked out that with a certain combination of weather radar and the Doppler navigational equipment in the C-130, you could literally track the airplane without any external references. I quietly practiced this with one of my navigators on every day supply dropping mission, flying down to within 200-500ft above ground level on his steering instructions, interpreted from the radar and Doppler equipment." | | The C-130B flown by the PAF used the APN-59B weather radar, which was a pretty decent piece of equipment, as long as it was used properly. It allowed the C-130 to fly in just about any weather and be able to avoid the particularly nasty storm cells. It did have some quirks, though, as Wing Commander Butt mentions next: | "One of the limitations of the radar is that it will topple if your angle of bank exceeds more than 45 degrees, which means that you lose your picture if your turn becomes too tight. But for training, I used to take off from Gilgit, at the far end of the Indus valley in Kashmir, and fly along on my navigator's instructions about 200ft above the watercourse, towards the foot of Nanga Parbat with my head down in the cockpit and the wingtips just clearing the banks.

Our normal dropping height is rather higher, about 1,000ft or so, but I wanted the crew to gain confidence in these techniques. We managed well enough, except that we still toppled the radar on occasions if the navigator's course corrections were too late and too large. We kept this to ourselves, however, and made no report at this stage to the air force.

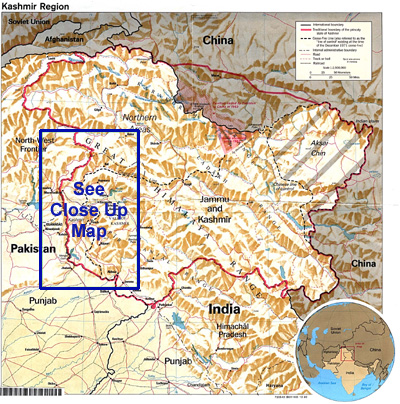

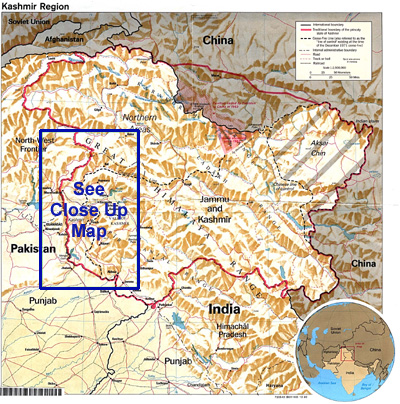

"The next step was to repeat this practice at night, which I did with the authorization of my station commander, Grp Capt Eric Hall. After takeoff, I used to shut down all aids except the radar, and head for northern Kashmir at about 20,000ft via Nanga Parbat, identifying various peaks on the radar en route. Our object was to let down blind into the Skardu Bowl, although we always planned on establishing visual contact with the ground before we began our dropping run. The civil aviation fellows at Skardu used to put the runway lights on for us, which we would use as our target for a simulated drop. We would then climb out and repeat the exercise." | | To put these words in the proper frame of mind, one needs to take a look at the area that they were flying. The Kashmir region of northern Pakistan and India has to rate as one of the most difficult areas for flying.

Overview map of the area. Close-up on Page Two.

The valleys they are flying through are pushing the limits of flying without oxygen, and the mountain peaks towering around them shear into heights above 20,000 feet. Nangar Parbat has been mentioned, and among the other mountains of the region is the famous K2. To be flying in this area in daylight is impressive; nighttime flying demonstrates pure courage. Wing Commander Butt demonstrated this courage repeatedly, and passed it on to his crews. | "When I told the station commander that I was ready to demonstrate the feasibility of night dropping in the mountains he found it hard to believe, but he came up with me once or twice and saw for himself. Three or four of my best crews practiced similar techniques, and I was then able to hint to the C-in-C that if the need was urgent enough, the night dropping of supplies might just be possible. I requested to be allowed to do the first operation, however, with a crew of my choice.

"With his encouragement, I took a high-altitude look at the area of the proposed clandestine drop in Indian-held Kashmir during the daytime, from a B-57, taking care not to cross the cease-fire line. I couldn't see much, however, because of cloud, although from about 50 miles away, the valley in which the DZ was situated seemed to be about three to four miles wide. We settled a date for the first drop to Qasim force, initially on 22 August, then changed to 23 August, my wife's birthday.

The day before, the C-in-C said that he wanted to be picked up to attend the briefing. As soon as I heard that I knew what was in his mind.

"Sure enough, at the briefing, which I conducted, AVM Nur Khan announced his intention of accompanying us, which necessitated some change in plan.

Originally, we had arranged to fly with civilian clothes beneath our flying overalls, and if we lost an engine or ran into trouble so that we couldn't climb out from the DZ, we had planned to try and join up with the Mujahids and fight our way out. But with the C-in-C on board, I cancelled the instructions about bailing out in the event of trouble, and briefed the crew on the basis of attempting a low-level exit in an emergency over the lake towards Muzaffarabad. The crew were all armed as usual, but the Air Vice Marshal refused to take a revolver." | | The concept of having the Commander in Chief of the Air Forces flying along on a mission, and a dangerous one as this, is pretty much unheard of, but this kind of attitude was typical of AVM Nur Khan. Malik Nur Khan has had an impressive career, starting back in the Second World War. He originally flew with the Indian Air Force, which led to some interesting circumstances. One of his classmates of his navigation class later turned out to be the C-in-C of the Indian Air Force in 1970. After W.W.II, Nur Khan returned to Delhi and found the country in upheaval. He made the decision to side with the Muslims and transferred to the fledgling Royal Pakistan Air Force, becoming Pakistan's first Air Adviser in London. This position allowed him to choose the best possible equipment for the building up of the Air Force. He was also involved in the Americanization of the PAF, and used his power to bring in the F-86F Sabre, a decision whose importance was shown in the 1965 war. His ability to lead his men well came partly from his ability to fly with them. Nur Khan made sure that he was kept current on all the planes that came into the PAF, including the new (in 1965) F-104A. This endeared him to the pilots serving under him, and made him a very popular leader, which is why Wing Commander Butt knew that the AVM was going to come along on this mission, even before Nur Khan mentioned it. | |