|

This site is best

viewed at 800x600

and 16 bit color.

| |  | | With the Air Vice Marshal now part of the crew, little was left except to load the C-130 up and prepare for the mission. This was undertaken with the usual skill of the loadmasters, and by the night of the 23rd, all was ready. Wing Commander Butt resumes his story: | "We took off from Chaklala, Rawalpindi, soon after 0200 hours, with 28,000lb of guns, rations, ammunition and other supplies and, at my request, an ELINT B-57 flown by Sqn Ldr Iqbal was arranged to fly at 40,000 feet to monitor the Indian radar, although I was quite convinced that the IAF had no capability to operate their fighters in that area. But we picked up indications of the Indian radar at Jammu being switched on as soon as we entered the area. The B-57 was also intended to act as a vital RT link in code with our own GCI, since we were out of direct VHF range with the ground stations because of the high terran, all around. Finally, it was scheduled to report on weather conditions for a final go or no-go decision.

"As it happened, and despite reports to the contrary, the weather in the mountains was such that normally I wouldn't have taken off during daylight for this sort of mission, but this was an emergency. Soon after take-off, we entered cloud at 12,000ft, emerging on top at about 26,000ft, and we did not see the ground again before the descent. Even Nanga Parbat was not visible, and the Shardi turning point had to be found and identified by dead reckoning plus interpretation of the radar picture.

From Shardi, which is the entrance to the valley of Srinagar in Indian-held Kashmir, we were required to descend south-east from 26,000ft to 14,000ft within about 2 minutes, speeding up to 260 knots to let down at 5,000ft/min or so, depressurizing in case of battle damage. The intention was to pick up the large Wular lake at Srinagar on radar, and then to come down below cloud for visual contact to reach the IP or set-course point of Bandipura. If I remember rightly, it was about 8.7 to 9 miles from Bandipura to the "Qasim" DZ on a track of about 170 degrees." |

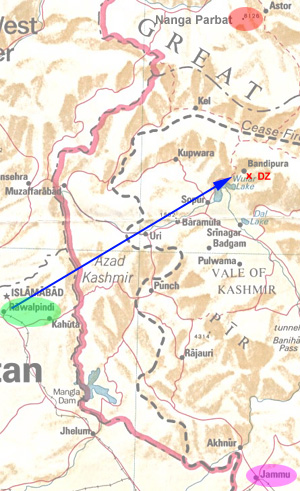

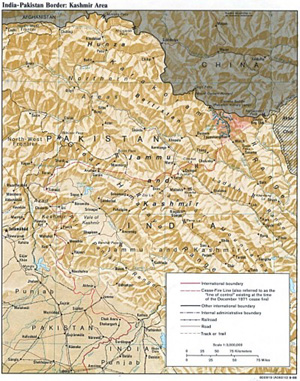

Close-up of the flight area, with Rawalpindi,

Jammu, and Nanga Parbat highlighted.

| "We were still blind when we began our let-down, and I added one degree to the steering instructions passed on by my navigator, Flt. Lt. Rizwan, to stay well clear of the hills each side of the track, extending up to 13,500ft. It was also important not to overshoot Bandipura at 14,000ft, since it was backed by a mountain 16,000ft high. But we came out over the lake in thin cloud and haze, and, although it was pitch black, we got the vital visual pinpoint on Bandipura.

"From then on, our flying had to be extremely precise to ensure an accurate drop. One of the problems was that to avoid overshooting, we had only 43 seconds to reduce our speed from a tremendous 260 knots to the maximum for ramp opening of around 148 knots. From then onwards, no variation in speed was permissible in an accurate drop was to be made, but I was quite certain that we were not going to have a smooth ride. DZ altitude was about 12,000ft above sea level, but between the IP and the target, at the predetermined dropping height of 1,400ft above ground level, while staggering along with the ramp open and flaps down, we again ran into turbulent cloud and snow. Four or five miles to our left was the 16,000ft peak, and our only available clearance was over the ridges to the right down the Srinagar valley. Fortunately there was little wind, as it was snowing, and only two track corrections were needed during the run in.

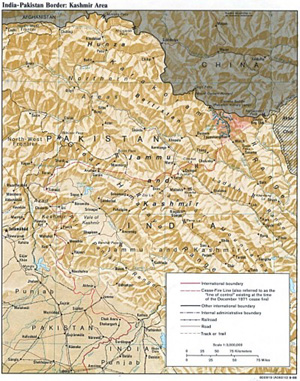

"When only a minute or so short of the DZ, still at 148 knots, turbulence in the storm cloud, with accompanying lightning, was so severe that the aircraft's speed dropped to below 100 knots and I couldn't maintain course accurately enough to continue. I therefore announced my intention to abort this run, but the C-in-C immediately suggested we should make another try. I straightaway opened up to emergency power and told my crew to close the ramp and clean up the aircraft. With its heavy load, the aircraft climbed very sluggishly and when I told my navigator to re-establish contact with the lake he had to wait until we had cleared the surrounding mountains. We had to do more of a chandelle or a wing-over than a climbing turn since I couldn't go further without being bothered by one peak and there was a ridge on the other side hemming us in." | | To put this in a proper frame of mind, take a look at the two following maps. The first one shows a relief map of what this area looks like during the day:

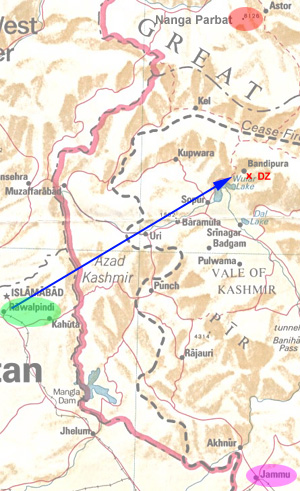

And this is what it looks like at night:

All of this flying had to be done while maintaining the proper attitude so as to ensure that the radar would not lose its picture. This means that all the turns had to be less than 45 degrees in bank. That, coupled with the extra 28,000lb of weight in back, made for a very interesting ride through the mountains on a pitch black night. | "We regained radar contact with the lake and identified Bandipura visually in position for another run. This time, I came down 200-300ft lower after reducing speed and opening the ramp, in an attempt to clear the cloud and turbulence, but I also told the navigator to prepare to drop blind, on timing and with the help of radar. We missed the turbulence on the second run, although we were again in cloud, and didn't see anything until almost at the end of the nine-second time count for the drop. Just as the navigator counted down to "three, two, one, NOW", the clouds parted for a moment, and there in the blackness the C-in-C and my co-pilot saw the twinkling lights of three of the bonfires marking the DZ. They were directly underneath us, which meant we had delivered all our load successfully." | | Afterwards the PakArmy confirmed the drop, and stated that it was within a half mile of the DZ. After flying through the valleys and avoiding the mountain peaks on a pitch black night, flying through clouds, turbulence, and snow, Wing Commander Butt completed his mission with incredible accuracy, especially for a blind drop. These tactics of using the weather radar as a terrain radar continued on, and several more successful night drops by PAF C-130s were made to the beleaguered troops in Kashmir. For his efforts that night, Wing Commander Zahid Butt was awarded the Sitara-e-Juarat. He is also now a member of the Order of the Golden Spheres. | |